By Oluebube A. Chukwu.

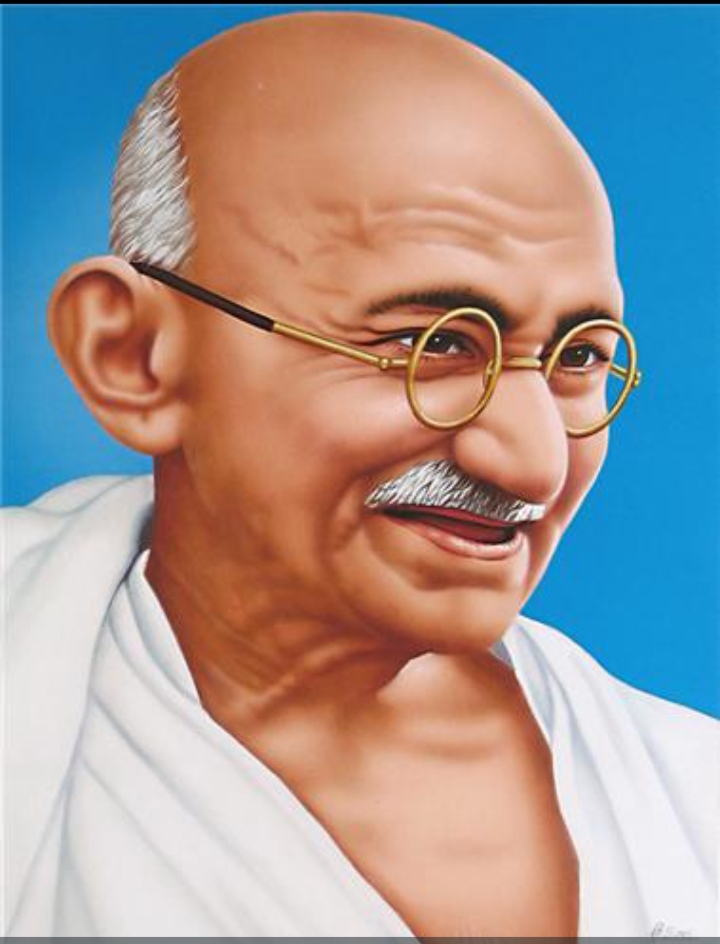

The name Mahatma Gandhi resonates far beyond the borders of India, standing as a symbol of moral courage, visionary leadership, and the power of conviction over coercion. His story is not merely one of political triumph but of the triumph of ideas, of the resilience of the human spirit against structures of oppression, and of the pursuit of a just and egalitarian society. In treating Gandhi as a concept, one cannot escape the weight of what his life teaches, especially when held against the chronic failures, contradictions, and missed opportunities that have characterized much of post-independence Africa. For African leaders who continue to wrestle with governance crises, corruption, and fragile democracies, Gandhi is not simply an icon of another continent’s past but a brutal mirror of what could have been and what still can be.

At the core of Gandhi’s philosophy was service. He was not driven by the hunger for wealth, the obsession with personal power, or the intoxication of authority. His life was lived with remarkable simplicity, a deliberate renunciation of the trappings that define political leadership in much of Africa today. The homes, convoys, luxury estates, and bloated entourages that surround African rulers stand in sharp contrast to the austere lifestyle of Gandhi, whose power lay not in material symbols but in moral authority. For a continent that bleeds from the wounds of elite greed and political excess, this stands as the first brutal lesson: leadership is not about accumulation but about sacrifice.

Gandhi understood that legitimacy comes not from coercion or manipulation but from trust. His struggle for freedom was anchored on the belief that people must be carried along, that their voices and dignity must be central to the political process. In Africa, decades after independence, the distance between rulers and the ruled has widened into an abyss. Elections, in many states, have become rituals of fraud rather than moments of renewal. Leaders cling to power through the machinery of manipulation rather than through the organic trust of their people. The consequence is evident in recurring instability, coups, and civic unrest across the continent. Gandhi’s insistence on participatory leadership is therefore not merely a moral principle but a practical formula for stability, which Africa continues to ignore at its peril.

Nonviolence was the heartbeat of Gandhi’s struggle. He proved that profound change does not always come from the barrel of a gun but from the moral weight of peaceful resistance. This philosophy disarmed empires and humbled aggressors without replicating their violence. Yet, African leaders and liberation movements, after winning independence, too often fell into the temptation of violence—against opponents, against citizens, and against democracy itself. Instead of nurturing a culture of peaceful resolution, states in Africa became theatres of military coups, civil wars, and authoritarian crackdowns. The brutal lesson here is simple: violence breeds cycles of destruction that no amount of nation-building can quickly repair, while nonviolence offers a moral and political foundation for enduring peace.

Gandhi’s leadership was never about self. He was more concerned about building institutions and awakening the conscience of society than about perpetuating himself as an irreplaceable figure. In Africa, the reverse has often been the case. Leaders build cults of personality, rewriting constitutions to extend tenure, silencing critics, and treating the state as private property. Institutions remain weak, dependent not on principles but on the whims of individuals. This personalization of power explains why many African states crumble when one strongman falls, because the institutions were never allowed to grow strong. The Gandhi concept teaches, brutally and without compromise, that a leader’s greatness is measured not by how long he stays in power but by how strong the institutions he leaves behind are.

Another piercing lesson is humility. Gandhi’s charisma was not flamboyant; it lay in his authenticity. He wore his humanity openly, embracing his flaws even as he carried immense responsibility. African leadership culture, however, is marred by arrogance, detachment, and denial. Leaders often treat citizens as subjects rather than stakeholders, and governance becomes an affair of command rather than dialogue. This attitude not only alienates the people but also erodes the legitimacy of government. Humility, as Gandhi practiced, disarms critics and fosters dialogue. In a continent where insecurity festers, economies falter, and trust in governance continues to diminish, humility could be the bridge between authority and legitimacy.

The economic dimension of Gandhi’s vision also strikes a chord. His emphasis on self-reliance, on building from within rather than being perpetually dependent on external powers, is particularly relevant for Africa. More than six decades after most nations attained independence, the continent remains entangled in dependency, relying heavily on foreign aid, foreign expertise, and foreign validation. Development plans are too often shaped in the capitals of donor nations rather than in the aspirations of local communities. The Gandhi lesson here is harsh: no nation can be truly free if its economic future is perpetually outsourced. Africa’s leaders, instead of feeding a culture of dependency, must summon the courage to invest in self-reliance, innovation, and indigenous industries.

There is also a moral lesson in the way Gandhi lived as a servant of his people. He derived his strength from listening to the poorest and most marginalized, making their struggle his own. In contrast, African leaders too often remain cocooned in privilege, insulated from the daily struggles of the citizens they govern. When policies are crafted, they are filtered through the lens of elite interests rather than the burning needs of ordinary people. The disconnect is glaring and destructive. Gandhi reminds African leaders that leadership is not an escape from the people but an immersion into their struggles, fears, and aspirations. To ignore this is to betray the very purpose of governance.

Corruption, perhaps the most enduring ailment of African politics, also finds its rebuke in the Gandhi concept. His personal life was marked by integrity, by a refusal to exploit power for private gain. By contrast, corruption in Africa is not only pervasive but systemic, eating into the fabric of governance and strangling opportunities for the youth. Every scandal, every misappropriation, every siphoned public fund is a brutal betrayal of the future. Gandhi’s moral discipline is a reminder that leadership without integrity is nothing but legalized looting, and societies cannot prosper under such conditions.

But perhaps the most haunting lesson of Gandhi lies in the contrast between the liberation dreams of Africa and the current state of many nations on the continent. At independence, Africa’s skies were filled with hope, with songs of freedom and promises of prosperity. Today, too many nations remain trapped in cycles of poverty, debt, conflict, and underdevelopment. The vision of freedom has been squandered, the promise of independence mortgaged by poor leadership. Gandhi’s example calls out across time, demanding a return to values, to purpose, to the understanding that leadership is not about the ruler but about the ruled.

For African leaders, to ignore the Gandhi lesson is to invite history’s harsh judgment. It is to continue on a path of squandered opportunities, of instability, of betrayals of the people’s trust. Yet, to embrace the lesson is to find a pathway to genuine renewal, to rebuild the social contract between governments and the governed, and to chart a future that honors the sacrifices of past generations. The choice is stark and the consequences are unforgiving.

Gandhi, when treated as a concept, transcends geography. He ceases to be only India’s icon and becomes a universal reference point for leadership. For Africa, a continent still in search of its true voice, his life and philosophy present a brutal but necessary mirror. It is a reminder that greatness in leadership is not measured by wealth or the length of tenure, but by service, sacrifice, humility, integrity, and the capacity to lift a people into dignity.

The story of Gandhi is therefore not one to be admired from a distance, as a tale belonging to another land. It is one to be internalized, interrogated, and applied. Every African leader who truly seeks to govern with purpose must confront this mirror, must ask whether their leadership reflects service or selfishness, humility or arrogance, institution-building or power-hoarding, peace or violence. In this confrontation lies the possibility of redemption for Africa.

Gandhi’s legacy, therefore, is not gentle. It is a brutal lesson because it strips away excuses, it tears down the illusions of grandeur, and it exposes the emptiness of power without purpose. It demands accountability, humility, and vision. For African leaders, it remains a call to conscience, a challenge to either rise to greatness or remain trapped in mediocrity. The time for excuses has long passed. The brutal lesson of Gandhi is waiting to be learned, and the future of the continent depends on whether its leaders are willing to embrace it.

Oluebube A. Chukwu Ph.D, writes from Umuahia.